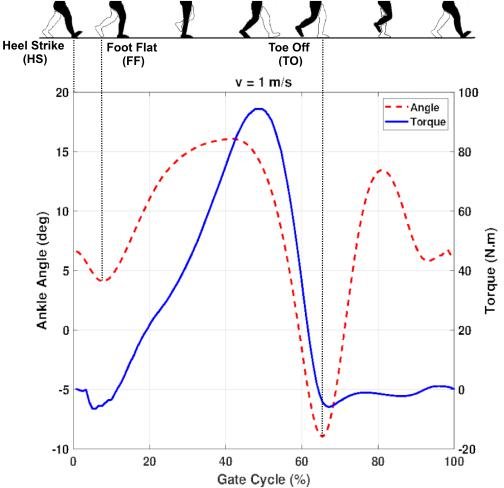

Behind every motorized prosthetic limb is a carefully engineered power system that quietly determines how comfortable, safe, and practical the device is for daily use. This project looks beyond control algorithms and focuses on the biomedical engineering challenges of powering a foot–ankle prosthesis, where efficiency, weight, and thermal safety directly affect the user.

Designing for the Human Body

Unlike industrial robots, a prosthetic device must move with the human body. That means the power system has to be lightweight, reliable, and efficient enough to last an entire day without overheating or frequent recharging.

For this motorized foot–ankle prosthesis, the key design goals were:

Choosing the Right Battery

Battery selection plays a major role in user comfort. Oversized batteries increase mass, while undersized ones limit mobility.

Through energy calculations based on typical walking patterns, the optimal balance was found to be:

This configuration supports a full day of use without compromising comfort.

Efficient Power Conversion

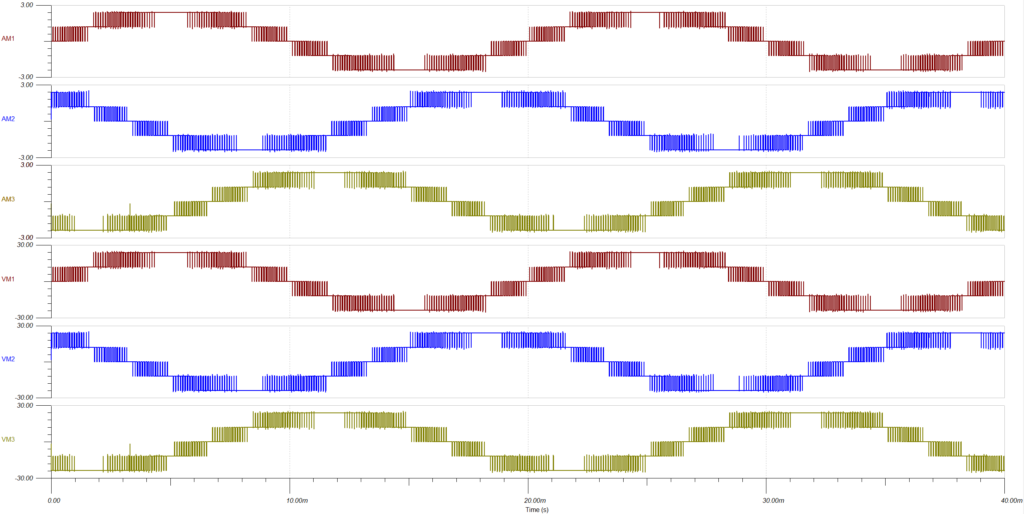

Once energy is stored, it must be converted efficiently into mechanical motion. To evaluate this, the LMGXXXX inverter from Texas Instruments was analyzed using simulation tools.

The results were well suited to our biomedical use:

High efficiency at this stage reduces heat generation and extends battery life—both critical for wearable medical devices.

Exploring Alternative Inverter Designs

Multi-level inverter topologies were also explored due to their ability to produce smoother electrical waveforms.

While these designs achieved lower harmonic distortion (0.82%), their efficiency dropped to 59.46%.

In a prosthetic application, this trade-off is not acceptable, as energy loss translates directly into reduced operating time and increased heat.

Final Thoughts

This project highlights how deeply biomedical engineering is tied to user experience. By selecting a 24 V, 10 Ah battery and a high-efficiency inverter, the prosthetic power system meets practical requirements for comfort, safety, and daily use.

Although advanced inverter topologies show promise, this study reinforces a key principle in medical device design: what works best on paper must still work best on the human body.